(NewsNation) — Sabrina Davis, Richard Waldherr and Michael Whittier live in different states, work in different industries and belong to different generations, but all three share something none of them wished they had in common — alleged medical negligence has derailed their lives.

Due to a combination of state laws and previous court decisions, Davis, Waldherr and Whittier say they’ve been blocked from seeking justice.

florida’s ‘FREE KILL’ law

When Sabrina Davis took her father to the emergency room for a sore knee, she thought everything would be fine.

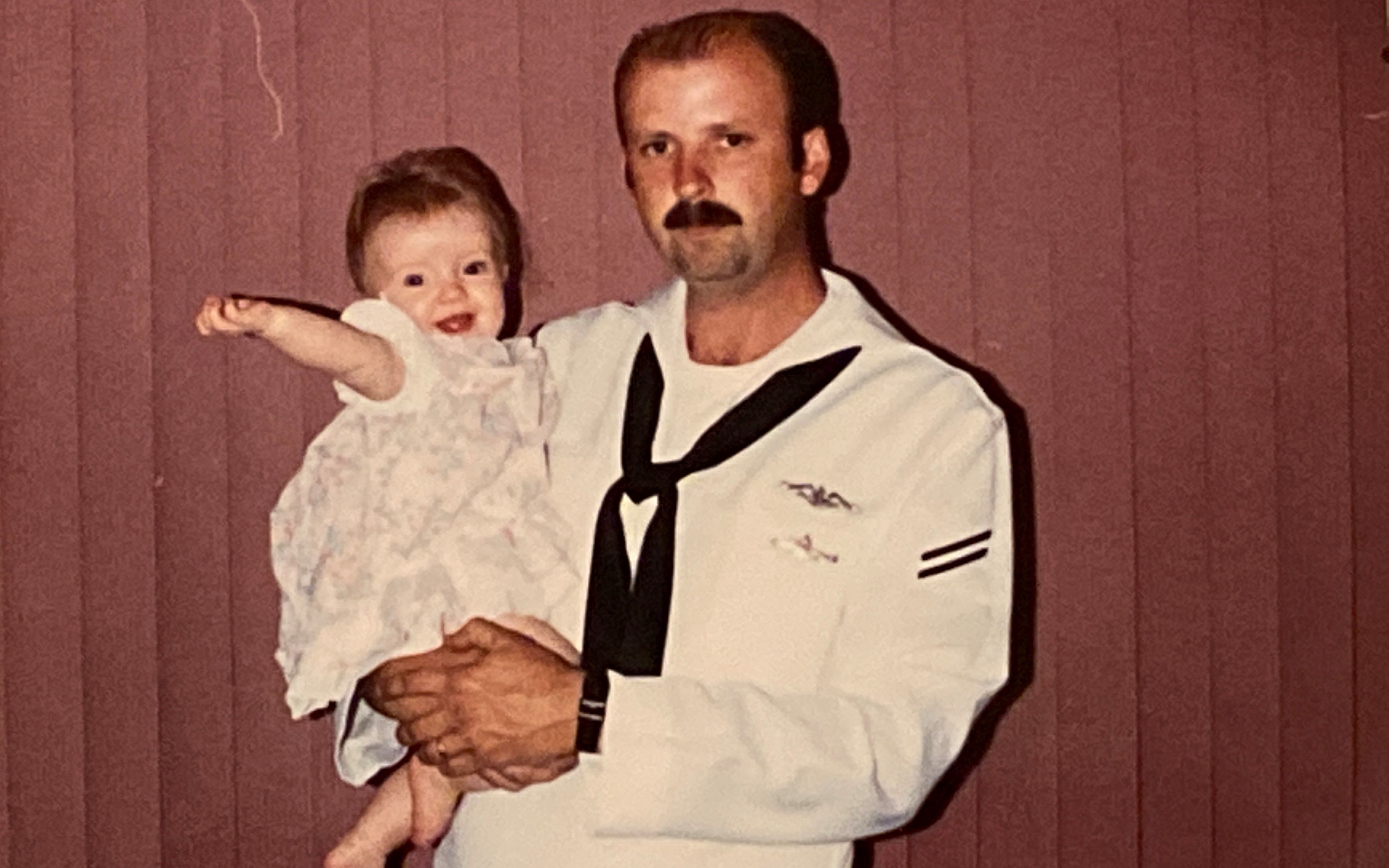

Keith Davis was a U.S. Navy veteran who had been through worse before and his daughter trusted the doctors at Brandon Regional Hospital outside Tampa, Florida where the family had been going for decades.

Sabrina Davis said her father reminded the doctors that he had a history of blood clots and took blood-thinning medication. She said his knee was swollen and hot to the touch so he asked for an ultrasound but hospital staff said it wasn’t necessary.

Her father was admitted to the hospital and put on bed rest. Five days later, hours before he was set to be released, he died at the age of 62 from a heart attack, according to his doctor.

His daughter thought there was more to the story. She paid for an independent autopsy that revealed what she suspected: a 9-inch long blood clot, originating in the same leg where her father had knee pain, broke loose and traveled to his lungs.

According to Sabrina, the doctor who performed the autopsy told her the death was preventable.

Armed with this new information, Sabrina Davis thought she could prove medical malpractice contributed to her father’s death.

But after meeting with multiple attorneys, she learned Florida’s wrongful death law prevents her from seeking justice.

In Florida, adults over the age of 25 cannot pursue damages for pain and suffering in wrongful death cases if a parent dies as a result of medical malpractice. Only spouses and younger children can pursue noneconomic damages. Since Keith Davis had neither, nobody could sue for those damages.

Some critics refer to it as the “Free Kill” law because of the dark contradiction it implies — a dead patient represents a significantly smaller financial liability to a doctor than someone who survives with severe injuries because the rule barring adult family members from suing for pain and suffering only applies to wrongful death cases.

Those in favor of the law argue that it helps keep insurance premiums low and makes Florida a better place to practice medicine because healthcare providers are more protected from lawsuits. But Sabrina Davis believes the law discriminates against people who are unmarried or don’t have kids.

“You can’t put this group of people in a category and say their life matters less,” Sabrina Davis said.

She’s shared her father’s story with Florida state lawmakers, who introduced a bill that would have changed the state’s wrongful death statute, making it possible for adult children to sue for medical malpractice.

But the legislation never advanced to a vote.

“I’m up against deep pockets,” she said. “I’m up against these lobbyists who work for insurance companies or doctor groups and they don’t want this law to change.”

For Sabrina Davis, it’s not about the money.

“I don’t want anyone to have to feel or go through what I have felt and been through,” she said. “My dad did not deserve this. He should still be alive.”

‘an iron curtain of protection’

Tracy Waldherr died after complications from a routine foot surgery at a Milwaukee, Wisconsin area hospital. She was only 41 years old.

“A parent is there when a child is born but you don’t expect to be there when they die in front of you,” said her father, Richard Waldherr.

The coroner determined she died from “hypertensive cardiovascular disease.”

Her father wasn’t buying it. She had no history of high blood pressure — it felt like an excuse to him.

So the retired police detective enlisted the help of a forensic pathologist and hired a third party to conduct a new toxicology report.

Those experts determined that Tracy’s cause of death was unclear and that a combination of drugs may have been a contributing factor. Richard Waldherr said she had been taking her regularly prescribed antidepressants and sleeping medication, in addition to post-operation opioid painkillers.

But due to a combination of Wisconsin state laws and court decisions, Richard Waldherr was told he couldn’t file a lawsuit to hold doctors accountable. His daughter was unmarried without kids and in Wisconsin, parents have no legal standing in medical malpractice cases once their children become adults.

On top of that, Wisconsin law caps the amount of money that can be recovered for noneconomic damages like pain and suffering in malpractice cases to $750,000, and even less for doctors employed by state-run hospitals.

Critics say the low payouts deter lawyers from pursuing malpractice cases.

“Under the current caps, no attorney is going to take a malpractice case because it’s just not worth it to them,” said state Rep. Christine Sinicki (D – Milwaukee).

Richard Waldherr thinks doctors in Wisconsin are behind “an iron curtain of protection” that prevents them from being held accountable for deadly mistakes.

Five years after her death, he continues to fight for justice, meeting with state lawmakers and sharing his daughter’s story.

“I think about her everyday…There’s unopened presents left at the Christmas tree,” he said. “Thanksgiving dinner, she’s not there — empty chair…We had phone calls, I would get Tracy saying ‘Hi dad!’ I miss that.”

the discovery rule

Michael Whittier was 53 years old when he received terrible news. A doctor told him he had prostate cancer and it had spread to his bladder and nearby lymph nodes. If it had been caught earlier, it may have been routine surgery but now it is life threatening.

The Maine grandfather was shocked. After all, he had undergone prostate exams in recent years and as far as he knew, everything was fine.

It turns out, there were warning signs but Whittier was never told. His medical records show he had dangerously high prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels years earlier but his primary care physician never mentioned it.

“It had three years to progress,” Whittier said. “I was angry. I was hurt.”

Whittier began meeting with local attorneys to file a malpractice lawsuit, but one after one they told him he had no case because the time limit to take legal action had expired.

In Maine, missed diagnosis victims have three years from the date malpractice occurs to file a lawsuit. Since it had been more than four years from Whittier’s abnormal test — not his cancer diagnosis — he was out of luck.

Maine law doesn’t apply the “discovery rule” in missed diagnosis medical malpractice cases — an exception that extends the time limit from the date the malpractice is discovered, not when it actually happened.

In other words, victims like Whittier could be out of time even before they know something is wrong.

Now, he faces a mountain of medical bills and fears what could happen if he passes away.

“I don’t want my wife to have to worry about this and I don’t want somebody else’s wife to have to worry about this,” he said. “It just seems quite unfair.”

Kelly Milan contributed to this report.

This story is part of NewsNation’s investigation into the tangled web of state medical malpractice laws that can make it difficult for patients and family members to file lawsuits against doctors they believe were medically negligent. Find all of our coverage on the topic here.