Andrew Nelson’s family has farmed in the rolling hills of eastern Washington state for five generations. Rows of wheat, peas, lentils and barley stretch across their 7,500-acre farm. Yet each spring, those hills provided constant stress when trying to predict frost — a task that’s eluded typical weather forecasting services.

“Sometimes the difference between the bottom of my hill and the top of my hill can be 10 to 20 degrees different,” he said. “We can very regularly get freezes that weather forecasts will never predict.”

Enter big data in a small package: On-the-ground sensors feed data into artificial intelligence algorithms that combine with National Weather Service data to predict how susceptible certain areas of his fields are to freezing.

“There’s so much risk in farming, and so many unknowns and uncertainty, that if I can make something a little less risky … that really helps me a lot,” said Nelson, who this year added the algorithms that kept him from fertilizing too early — which can damage plants.

These futuristic farms go by many names — smart or digital farming, or precision or data-driven agriculture — but an expanding number are using data and algorithms to inform everything from when to plant seeds to where to water to which techniques release the most carbon into the air.

According to a 2021 survey, 87% of U.S. agriculture businesses currently use AI, and the agricultural robotics market is predicted to reach $30 billion by 2026.

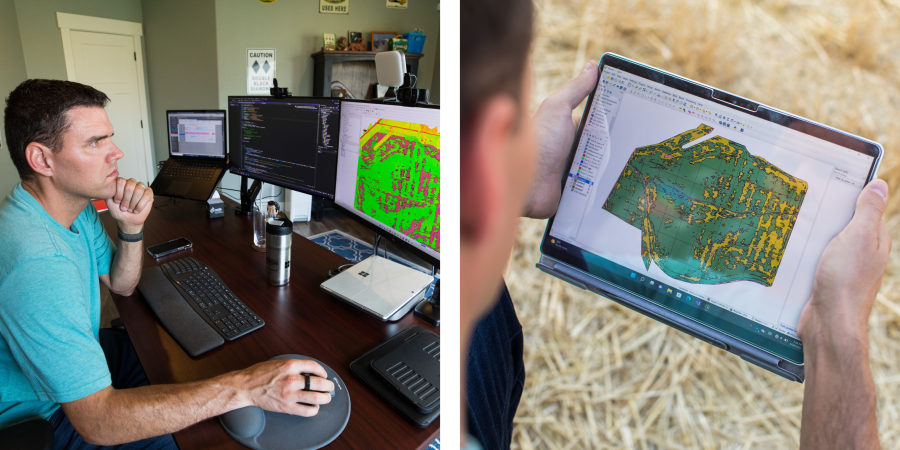

Nelson, who is also a software engineer, combines a program to remove clouds from satellite images through AI with another program that collects data from drone images and ground-based sensors together to create a model that can identify weeds. It allowed him to target herbicide only to the areas that need it — and spend 38% less.

Nelson’s farm has been a testing ground for Microsoft agricultural research projects since 2017, allowing Microsoft to prove their technology can work in the real world, said Ranveer Chandra, managing director of Microsoft’s Research for Industry. This week, his team released a suite of open-source algorithms called Project FarmVibes.

Chandra said the goal is for researchers around the world to use it to develop data-driven technology for which farmers won’t need a software degree.

“We should be able to say what (a certain section of a farm) looks like right now, what it looked like in the past and what it would look like in the future … not just above the surface, but below the surface as well,” he said.

And the stakes are high.

“Given the food security problem right now, given the problems around climate change and water, we don’t have a choice but to start adopting these technologies really fast,” he said. “Working with Andrew, we’ve shown that (this technology) is mature, but the ecosystem needs to evolve.”

There remain challenges to mass adoption of this technology, most notably the digital and economic divide facing small farmers, particularly in developing countries. There are more than half a billion farms smaller than 2.5 acres worldwide, Chandra said, and less than 13% use any form of digital technology.

Even in the U.S., farmers need to recoup the cost of new technology within a year, Nelson said.

Pandora’s box

Until recently, smart farming has been limited to large businesses or researchers, those with strong internet connections and those who can afford to experiment, said Maanak Gupta, cybersecurity expert and professor at Tennessee Tech University. Yet as technology gets cheaper and connectivity more accessible, the “adoption in smart farming certainly opens up Pandora’s box of cyberattacks.”

The area of highest concern is data privacy (who gets to see it) and collection (who gets to keep it and where) — particularly in an industry where soil composition or seed yields is considered proprietary information.

“Let’s suppose before doing a water sprinkler, your machine measures soil (moisture) is too low. So that will automatically trigger on a soil water sprinkler,” he said. “But what if that is false data? What if your soil already had enough and you don’t need any water anymore? That is going to completely ruin their entire field.”

“When somebody can disrupt the entire economy of an agriculture-dependent nation … attacks in a well-coordinated manner can really be referred to as agroterrorism,” he added.

It also has huge implications for the entire food supply chain, which is already being shaped by insights from algorithms and big data.

“We should be careful about what data gets in the hands of what people. Food security is critical infrastructure for the country,” Chandra said, adding that Project FarmVibes currently does not collect or store data.

Key to finding solutions, both Gupta and Chandra said, is giving farmers control over the data collected on their farms.

“(Data-driven insights) will help farmers be more profitable. This helps consumers become healthier as well. And it just makes the entire supply chain much, much more efficient (reducing) food waste … helping address food security,” Chandra said. “Those all are things that data-driven agriculture could light up.”