How Cincinnati is buying homes in bulk to keep them cheap

Testing on staging11

CINCINNATI, Ohio (NewsNation) — When almost 200 single-family homes came on the market this year, Cincinnati’s Port Authority made a bold move: It outbid 12 large real estate investors and became a landlord.

It was Cincinnati’s counterattack to skyrocketing housing and rental costs, which it blames in part on the big investment funds it beat back during the January 2022 sale. The city will now rent the homes at an affordable price with the hope of transitioning the renters into owners.

Solving rising housing costs is a challenge across America. Rents across the country are on average 17.1% higher than last year. In March, rents increased in 93 of the nation’s 100 largest cities. In Cincinnati, it increased by 28.4%.

There are other factors driving up housing costs. Pandemic-era problems of supply chain and expensive raw materials remain problems. A rush to get into the short-term rental business like Airbnb also hurts. And investment funds point out there are plenty of vacant homes that could be refurbished by cities and others.

But for places like Cincinnati, the fact that institutional investors are now more often competing with (and beating) everyday Americans for single-family homes is something they can change.

“We’re ripping off the people in our country if we say only a few … get to make a lot of money by controlling hundreds of thousands of houses,” said Laura Brunner, the CEO of the Cincinnati Port Authority, the city- and county-government agency used to buy these homes.

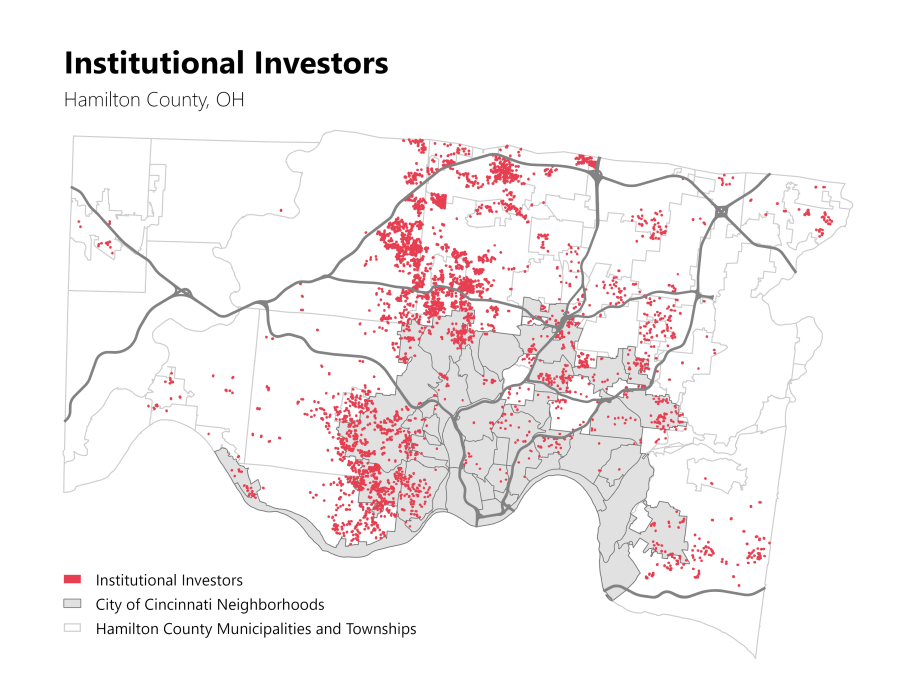

In the past five years, 4,000 Cincinnati-area single-family homes were bought by just five out-of-town investment companies, according to The Port’s analysis. The plan will interrupt an accelerating and disturbing trend: turning single-family homes into rental properties — then hiking up rents and scrimping on maintenance, she said.

The result is “a real tsunami of negative impacts,” Brunner said, decreasing home values for those already living there and less stability for low-income renters.

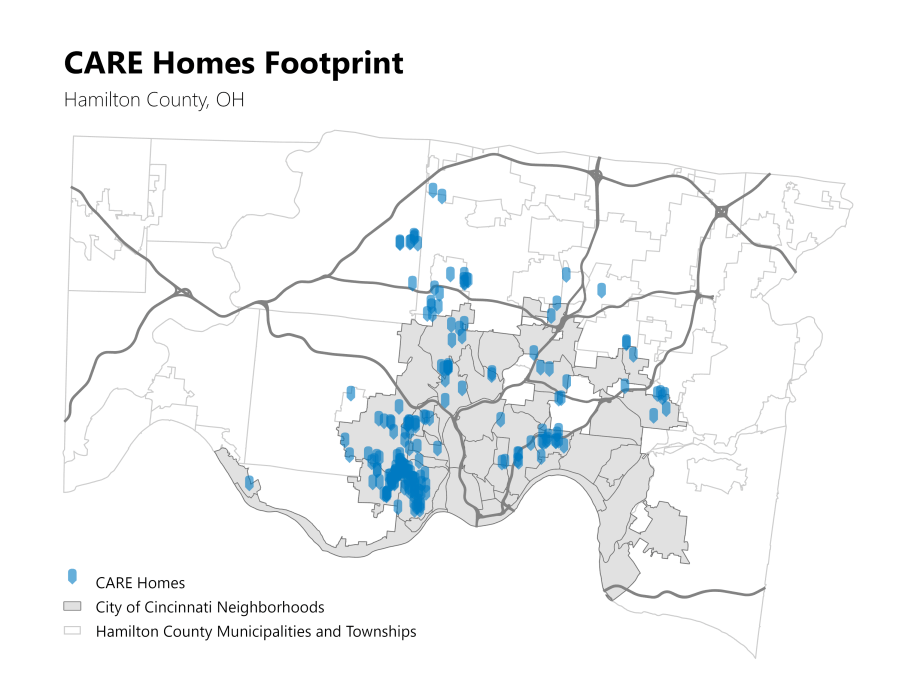

The Port says buying these 194 single-family homes for $14.5 million will keep these stand-alone homes affordable and well-maintained in the greater Cincinnati area. Their goal is that the renters in these homes transition into owners. And that’s important because owning a home is one of the most significant factors in building wealth and stabilizing neighborhoods.

Billions in single-family homes

Cincinnati is not alone. In just one quarter of 2021, institutional investors (a company, like a hedge fund, that invests on behalf of others) spent $64 billion buying single-family homes across the U.S. The neighborhoods these investors target are much more likely to be low- or middle-income and majority-Black, -Latino or -Asian, than white and affluent. Some of the largest rental investors are 18 percent more likely to evict their residents than mom-and-pop landlords.

And several studies of the single-family real estate market showed this leads to wealth flowing from the pocketbooks of American families into those of institutional investors.

“It is seductively attractive to invest someplace else. You might be the enemy inside of our community, but nobody knows you. So you’re not subject to the criticism that media or politicians can put on you,” Brunner said. “The anonymity that comes with this institutional aspect I think makes it even more evil.”

A common way cities try to address this is by establishing a community land trust, where governments or a nonprofit retains ownership of a piece of land while selling the house on it. Buyers promise to sell it to other low-income families. Land trusts across the country, including ones in Cincinnati, have succeeded in keeping housing in a targeted area affordable.

But no one has tried to buy and sell homes at the scale of Cincinnati, which is “a game-changer for the housing market,” reporter Konrad Putzier said on a recent Wall Street Journal podcast about the acquisition. “If other cities follow the example of the Cincinnati Port Authority, it could really have an impact.”

In Ohio, a port authority is an economic development entity run almost like a nonprofit, with a board representing both the city and the county. This gives it the flexibility to partner with neighborhood development groups — providing provide potential owners with much more assistance, including financial literacy and homeowner training, and down payment grants.

In this model, people can work toward owning a home over months or years while living in a home that’s well maintained — widening the circle of who can buy and the quality of what’s available. Owners will only be required to live on the property for five years.

“We can be patient,” Brunner said. “But what we also have to do is not take houses off the inventory so that investors can make a lot of money.”

But how large is the impact?

Still, the small number of homes in the program is a “tiny drop in the bucket,” said real estate expert Don Walker. According to 2021 census data, there are 380,769 homes and apartments in Hamilton County where Cincinnati is located.

“Will it keep rents affordable? Probably, no change,” said Walker, who is the CFO of John Burns Real Estate Consulting. Meanwhile, as high-income, white-collar millennials flow out of expensive cities like San Francisco and New York, they bring a willingness to pay top dollar to rent a white picket fence and backyard.

That willingness, mixed with a perfect storm of supply chain slowdowns and decades of under-building housing, is driving up prices. And it’s not likely to slow until 2025.

“Supply is not able to keep up with demand,” Walker said, adding it is deceptive to blame big investors for inflation in the housing market. According to John Burns’ data, large investors own just 6% of homes nationwide. And many other factors can speed gentrification in certain neighborhoods, from a large mall going in, to a downtown redevelopment project.

“(Investors) are taking a risk to buy that home,” he said. “They’re fixing it up to create a better place to live. If we didn’t have that in the market, no one would supply housing.”

Instead of trying to buy houses out from under investors, he argues, local governments should focus on bringing vacant housing — which in the greater Cincinnati area is about 9% of homes — back on the market. “More housing is the solution to affordability,” he said.

Brunner agrees more housing is needed but says it’s important to look at who gains wealth when large investors buy up single-family homes, adding The Port has stabilized the cost of housing and lessened the risk of eviction for 150 families.

“At a macro level, this is a case of the market being very efficient,” Brunner said. “What we believe our job is is to follow behind the market and say, ‘No, you might be really efficient, but it’s not moral.’”