Do more visible police help deter crime?

- Philadelphia posted pairs of police officers nonstop at certain hot spots

- This strategy may have deterred people from committing crimes

- The strategy is expensive and may have social costs as well

PHILADELPHIA, PA – JANUARY 05: A police officer stands watch near the scene of the fatal fire in the Fairmount neighborhood on January 5, 2022 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. A fire killed 13 people, including seven children, in a Philadelphia rowhouse on Wednesday morning, officials said. (Photo by Hannah Beier/Getty Images)

Testing on staging11

(NewsNation) — A policing program that began and ended nearly 20 years ago may still teach new lessons about policing and crime.

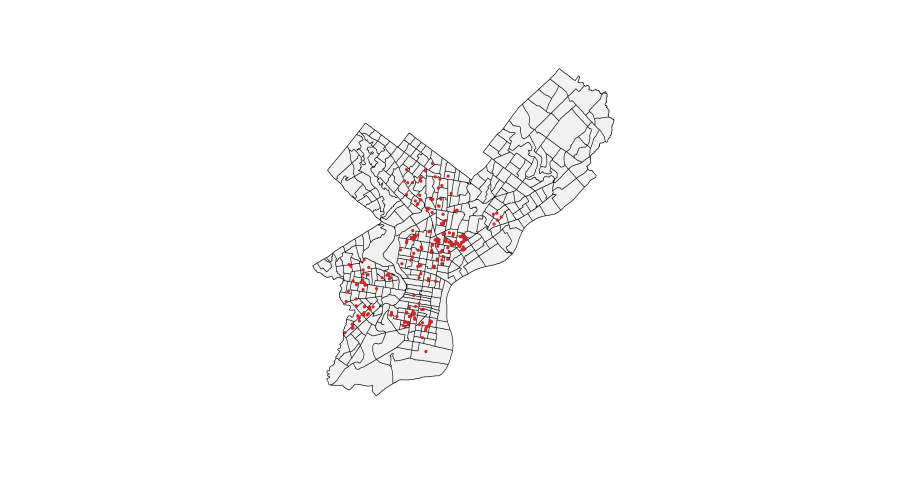

In May, 2002 the city of Philadelphia implemented a new crime-fighting program called Operation Safe Streets. The initiative deployed a pair of uniformed police officers at several hundred locations that were known to be hotspots for the illegal drug trade. This approach is sometimes called “hot spots policing.”

This staff-intensive initiative, which lasted less than two years, offered nearly non-stop policing of problem areas. Some critics of the program worried that the constant police presence would intimidate residents.

The goal of Operation Safe Streets wasn’t to deter crime only through more arrests; the goal was to deter crime with greater officer visibility.

Researchers found it succeeded in reducing both drug and violent crimes in the areas targeted, and 20 years later, there is evidence it changed the minds of young people in those hot spots.

Harvard University researcher Rebecca Bucci examined how Operation Safe Streets’ emphasis on making police more visible had an impact on how residents thought about their risk of arrest, publishing a new study this year.

Using survey data gathered around the time Operation Safe Streets went into effect in Philadelphia, Bucci looked at how perceptions changed, particularly the risk of arrest. Everyone surveyed was a young person that had previously been arrested and involved with the justice system in some way.

Bucci found a substantial increase in the self-perceived risk of arrest after the initiative was in place.

“The general takeaway is their perceptions did go up… it’s about 13% compared to their perceptions before (Operation Safe Streets),” she said, adding that kids who have been arrested before usually see a 6% increase in perceived risk of arrest.

Although she can’t say for certain that this means that Operation Safe Streets reduced crime by increasing people’s perception that they would be arrested if they commit a crime, it does offer one possible reason for the program’s success.

However, Bucci did note the costs associated with this kind of policing strategy.

For one, it’s very resource-intensive. Police departments across America are dealing with staffing shortages, and this form of hot spot policing requires a constant presence in just a few places.

“This probably isn’t the most efficient use of police resources,” Bucci said. Indeed, by the summer of 2002, the program was costing the city as much as half a million dollars a week in overtime.

Also, maintaining a constant police presence in an area can polarize a community. She pointed to media accounts about residents’ response to Operation Safe Streets in Philadelphia.

In the first week of the program, The Philadelphia Inquirer interviewed residents about how they felt about the increased police presence.

“I feel safer sending my children to the playground now,” one mother told the paper.

But others were more critical “I’m all for getting rid of drugs,” one woman said, “but I should be able to go into the corner store without police asking, ‘What are you doing?’ Or telling you to get out of the store.”

Hot spots policing has had additional critics, who says stationing police nonstop in certain areas can lead to stigma.

Bucci added she didn’t have data on what the police who were involved in Operation Safe Streets were actually doing at each location, which could help understand what tactics used as part of the program was most effective.

Ultimately, Bucci argued, there needs to be more experimenting to figure out what works.

“Maybe we can do it at 100 hotspots or one officer at each place or 10 hours a day instead of 24, right? I think and kind of hope that the field and policing… goes to testing those things instead of just saying it’s all or nothing,” she said.