(NewsNation Now) — The view of the devastation of COVID-19 from the inside is far different than from the outside. In a political climate consumed by masks and relief money, a look behind the intensive care curtain finds unprecedented work and camaraderie, impossible sadness and even a little bit of hope.

From Wisconsin, to Iowa, to North Carolina, NewsNation visited with hospital workers, families and professionals whose lives have all been altered by the parade of illness and death which have underscored this unforgivingly endless and endlessly unforgiving year.

“I would say everything is different. Although I think we’re trained to work in a hospital, we never predicted we would be in anything like this,” said Dr. Ann Sheehy.

A changing way to practice medicine

Dr. Sheehy oversees the COVID-19 ward at UW Health University Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, where not just the medicine they practice has changed, but so too has the way they practice.

“We will never be the same,” she said. “This has changed completely how we think about medicine, thought about our routines, our true link to the public. I mean, really what we’re seeing now is directly related to the public response to this pandemic.”

Moreover, the unpredictability of the virus has made medicine even more challenging, with increases in cases happening now and intensive care units like the one at UNC Hospital in Chapel Hill, North Carolina at, near, and over capacity.

Dr. Shannon Carson is the chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

“So the number of ICU patients has doubled over the last two weeks, and the acuity of illness of those patients has gone up considerably,” Dr. Carson said.

NewsNation asked Dr. Carson if this scares these health care workers.

“Well, I think it, you know, frightens our team,” he said. “They’ve been working extremely hard on this nonstop and in this state since April. And I’ve been busy with it. And these people have been on the front lines the whole time.”

Treating COVID-19 patients day-to-day

NewsNation was granted unusual access to those frontlines where Dr. Sheehy, Dr. Carson and their teams fight these battles.

The day-to-day has changed for these doctors and nurses who spend stretches of time in the process of what they call donning and doffing, the careful putting on and taking off protective gear called PAPR or powered air-purifying respirators, that push air down so that inhalation is limited.

As nurses go from room-to-room attending to these gravely ill patients, they do so with risks like they have never before faced and they serve shifts on either side of a line of tape separating what this hospital calls low and high-risk zones.

“So currently this is just routine care for COVID infected ICU patients, with providers close to the rooms in personal protective equipment to keep them from becoming infected. On this side of this barrier, we are a safe enough distance from the rooms where infection is very low risk, so we wear a lower level of personal protection,” Dr. Carson explained.

But what happens on that high-risk side, the face-to-face care that is given, from respiratory rescue to the administration of medicine is what brings professionals like Chapel Hill nurse Alan Fanning to work every day, even as the virus swells.

“We’ve always taken care of sick people and that’s all we really want to do, but I think the resources are really stressed right now.”

Alan Fanning, Nurse in Chapel Hill, North Carolina

“I think we worry that we’re not going to be able to provide the level of care that we’ve been able to provide in the past. I haven’t seen that yet. But you know that that’s the worry,” he said.

Fanning fears what health care experts have forecast, a further case escalation from Thanksgiving which would be happening right now with more in the weeks to come.

“We’re already planning, the hospital’s already planning, for what’s going to happen a week or two weeks from now, following Thanksgiving,” Fanning said. “I think that’s been going on since day one, there are contingency plans based on what might happen. Until we run out of beds.”

In Madison, Dr. Sheehy fears the same.

“I would say that we need the public right now,” Dr. Sheehy said. “The health care providers are doing everything they can. The amount and the volume of patients who need us in the next month is directly related to what the public decides to do”

How rural hospitals are handling the pandemic

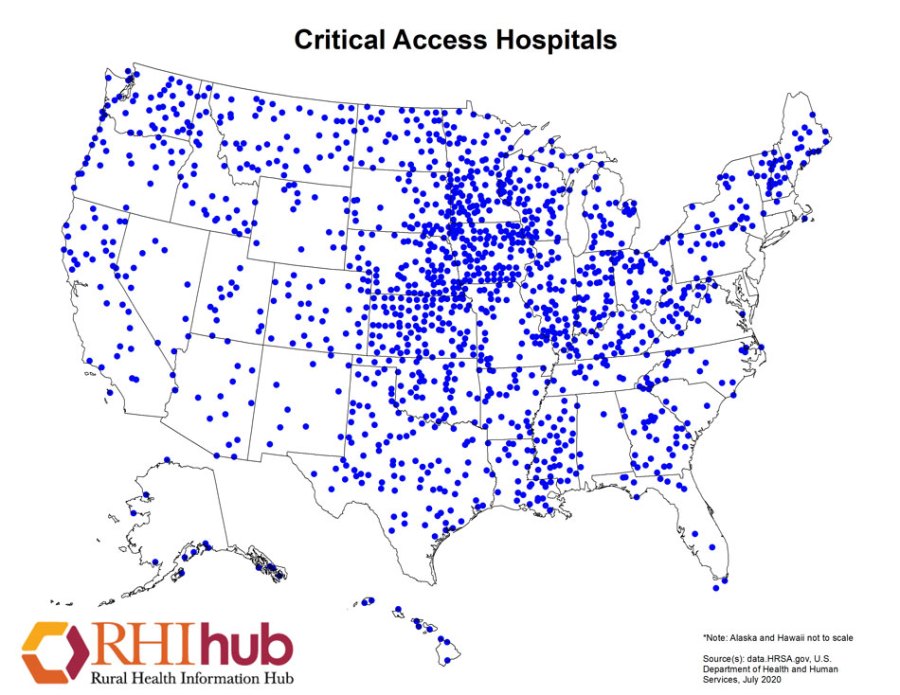

Even at a rural hospital like in Newton, Iowa, the fear is similar.

“If the surge gets much worse, we’re already kind of at our near capacity. There is not more surge that we can take,” said Chad Kelley, director of ancillary services at Mercy Hospital in Newton.

Kelley oversees emergency preparedness at Mercy Hospital, where the recent rise in cases is acutely felt.

“We want to help but when we’re taking up with not expected illnesses, a high surge of that, you know, there is a sense of tension and a sense of urgency,” Kelley said.

An urgency over which only so much can be done.

“We are positioned 30 miles from Des Moines, we have a county of 37,000 people,” he said. “We have staff just under 200. And so, by large and far, our resources are relatively thin.”

In rural hospitals, the COVID-19 care is no different from anywhere; however, those resources that Kelley mentions are a challenge that every one of these hospitals across America face.

Michael Shure: We are in Newton, Iowa, which is a smaller town. What is it that’s different here than you would find it a COVID wing in Des Moines or a bigger city?

Kelley: Our job is to stabilize the patient and get them to the center where their specialists as well as pulmonologist, neurologists, who can then take care of them. So, a lot of it comes down to resources.

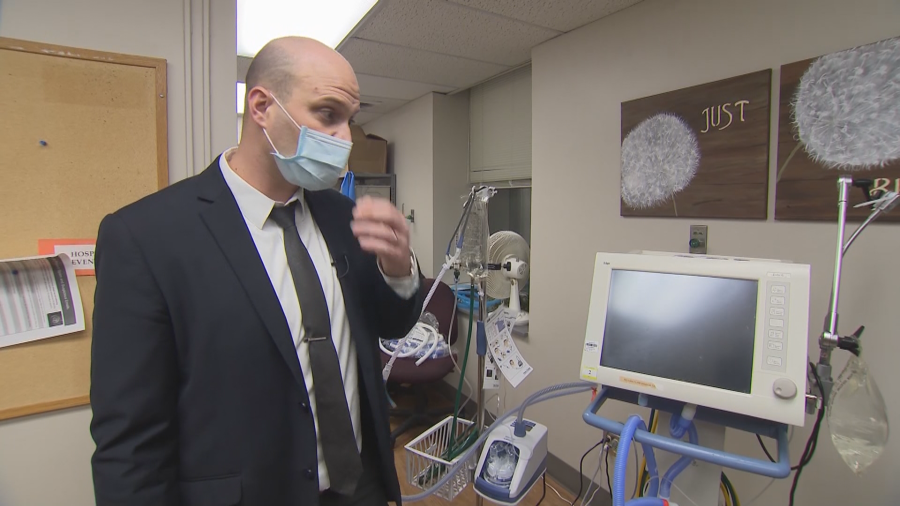

Perhaps the most vital of those resources in this pandemic is the ventilator, and they know that in Newton.

“This would be a prime example of a standard ventilator,” Kelly said. “You know, this one isn’t by any means brand-new, or, you know, the ‘Cadillac,’ so to speak, but it works for us. And we’re very thankful and grateful to have it.”

Many of these coronavirus patients are so severe that they need to be transported to Des Moines via helicopter. Iowa has a sophisticated network for bringing rural patients to a hospital like Mercy in Des Moines.

Matt Klein is a flight nurse at Mercy One Hospital in Des Moines, Iowa.

“We work with the tertiary facilities and transport these patients to Mercy or you know, any other major hospital in the state that requires advanced care that they’re not able to provide at the root level,” Klein said. “That’s our big part of that process. So, we’re just one small piece of this giant puzzle in regards to managing COVID patients.”

The helicopters provide relief to patients but also to the hospitals in the more far-flung parts of the Hawkeye state.

“The illness isn’t, you know, benign. Anyone can get infected, regardless of geographical location,” he said. “So, in the rural setting where there’s a smaller, Critical Access Hospital, that they’re limited with resources, specifically critical care needs. That’s where our involvement with this management of pandemic is critical.”

The lives lost and changed by the virus

Yet, while all the king’s horses have metaphorically mobilized to fight the coronavirus, the history will be written by those who survive the ravages of the disease and those who are survived by it—like these two women who lost two different men in their lives.

“We also joke that he was, he was the guy who always knew a guy, you know, if you needed something, josh would say, ‘Oh, I know a guy, I can get that for you,’” said Newton resident Sarah Muhs about her brother. “He was very well liked.”

Muhs is a schoolteacher in Newton, Iowa.

“There were times when, you know, I call my mom and ‘oh, he’s getting better. He’s feeling better.’ And he went to the hospital earlier in the week on a Monday because he, I think, he was having trouble breathing,” she said.

Muhs said the hospital sent her brother home with an inhaler.

“And then just kept going downhill and he went back to the hospital on that Friday and never came out,” she said.

Sarah lost her brother, 46-year-old Josh Glodo in August.

“My brother is so much more than a number.”

Sara Muhs

“He was a son, he was a dad, he was a brother, a cousin. He was a friend, he was loved by so many people. And, yes, he’s one person, but his death has affected so many people. Just the one person’s death, it’s changed my life, forever changed the course of my life definitely changed the course of his daughter’s life. My parents had to bury their only son,” she said.

Jamae Wierzba is an ER nurse in Madison, Wisconsin.

“That day, everything seemed to be going fine. He went home, went back to the office on Thursday, he just wasn’t getting any better. And my mom had mentioned that maybe he needs to start staying home,” she said about her grandfather.

The two met in her driveway as she was going to work.

“And he said, ‘hey, Jamae, what do you think? Do you think I have that COVID stuff that’s going around? He was very, he’s a very smart, knowledgeable man,” Wierzba said.

Both Midwesterners were touched in tragic ways by the coronavirus.

“His oxygenation dropped so fast, it was unreal,” she said. “How a life is taken so quickly because of this nasty virus.”

Jamae lost her grandfather at age 80 in October.

“One of the things that company is doing is in their email signature is, at the bottom there putting ‘remembering our gentle giant,’” she said. “I think that’s a really good way to explain him and to keep him in the spirit of the company.”

The strain on families who can’t be with their loved ones has been an unforeseen and brutal part of the pandemic.

“Every day, you’re talking to these families, and you don’t have a lot to say a lot of the times because it’s just time that they need,” said Nicole Parish, a registered nurse at UW Health in Madison.

The absence has been felt by those trying to save lives—

“It’s hard for them to sit there, you know, 24 hours a day worrying about their family member while we’re here working and not hear from us,” Parish said.

—to those who deal with end of life.

“Life is a rite of passage. And we all need to be able to support each other during that,” said Pete Gunderson.

He owns Gunderson Funeral Home in Fitchburg, Wisconsin.

“Zoom has been wonderful, FaceTime has been wonderful, but we use all of our senses. Anytime that we’re in emotional times. So that leaves out the touch,” he said.

As these stories are being told all over the country, so too are the stories of those who work, so that they need not be told.

Alex Martinelli is a nurse practitioner at UW Health University Hospital.

“Everybody, you know, in a way, they feel like they signed up for this, to take care of really sick people, for a lot of people is their calling, I think. And they didn’t hesitate. You know, of course, there were a lot of difficulties along the way. And it’s still very difficult. A lot of hard days.”

Martinelli has seen so much in his career but highlights the newness of this foe.

“I mean, we’re all working through this together,” he said. “I mean, it’s a novel virus, nobody’s an expert, by any means. Because many people want to be experts. There aren’t any.”

But there are different kinds of experts in these hospitals, like Jeffrey Kaether, an environmental services technician at the same hospital.

“To keep it simple, most people would say that we’re housekeepers of the hospital. So, cleaning non-patient and patient rooms, areas throughout the hospital,” Kaether said.

Environmental services technician is the fancy title for what Kaether does there, a vital job at hospitals everywhere.

Shure: You’re not a doctor, not a nurse, bringing medical relief, you’re not curing, but you’re filling another role? What is that role for you?

Kaether: I feel like, you know, we don’t have a role that’s up here. As far as people looking at it, you know, we’re more down here. But what we do is the most important thing here, because if I’m not doing the cleaning, as well as my co-workers, every single day, this place can’t be open. It’s not going to be safe, it’s not going to be sanitary, you wouldn’t want to come here if it wasn’t clean.

Responding to COVID-19 isn’t all about medicine in any hospital. Kaether revels in the relief he may be able to bring to an intensive care patient.

“I like to get to know them,” he said. “Obviously, I know why they’re here, but we talked about other things from that. So, while I’m cleaning, I can take their mind off why they’re here and talk to them about their family or what they’re into what they do on the outside.”

The medical professionals we spoke with lament the lack of care being taken outside of the hospital walls and wished that people got to see what we saw, and what they see every day.

“You’re making choices for other people and you have to think about whether or not that’s really fair, and would you want people making those choices for you? Because the worst-case scenario is right here,” Fanning said. “And that’s nothing I wish on anybody.”

“I understand the freedom viewpoint of the mask-wearing, but I think if we just take a step back, and just say he just was like everything else, there are battles to fight,” said Martinelli. “Maybe this is the one that we can just band together, and help each other out.”

“But we really, really need people to wear masks and forego those social gatherings, even the small ones, they’re just critical right now,” Sheehy said. “If we do that our systems may avoid getting completely overwhelmed. And we’re at the brink right now. We don’t have any more space. And we don’t have any more staff. And we’re begging for the public to understand that.”

Despite the background noise and those admonitions, the work of hospital staff like nurse Nicole Parrish is informed only by getting people better

“For me, I have to separate that,” Parrish said. “I feel like by the time you get to a room where I’m taking care of you, it doesn’t matter to me if you’re 30, 80. You believe in COVID? If you don’t, if you wore a mask, if you didn’t. If you’re an immigrant or a U.S. citizen, none of that matters to me at that point, I have to just separate it and you’re my patient, and I’m going to do what I can,” she said.

The day NewsNation was in Madison, the staff had placed a breathing tube in an elderly patient, a prisoner, who ironically had guards placed outside his room as other patients can’t even see family.

“You can feel the angst, you can feel the anxiety, they’re on the phone with on FaceTime with our families saying, ‘I love you and I hope I get to see you again.’ So that’s the part that’s like the scared part,” Parrish said. “On my end, I know that we take amazing care of our patients, and we’re going to do everything we can to get them off the ventilator. But you know, it’s probably a 50/50 shot once we intubate.”

Odds that Georgia NAACP board member Edward DuBose knows well.

“It was our anniversary, our 35th anniversary and she was saying ‘happy anniversary’ and I was telling her, ‘baby I’m sorry that I was not able to get us anything.”

Words DuBose uttered from an ICU bed in Georgia.

“She said ‘don’t worry about that. We have a lot of years to go,’ but I was so far gone. I told her now. ‘I’m not gonna make it this time. We won’t have no anniversaries’ and she got quiet, but I had to let her know based on where I was at. I felt that I was dying.”

DuBose is an ordained elder in the church and his faith, he said, is part of why he was in the hospital to begin with.

“At the very beginning, I was one of those people who didn’t believe in wearing masks,” he said. “I somehow, I covered it behind my faith, thinking that you know, somehow if you are a person of faith, the mask doesn’t pertain to you.”

If the virus tested his faith, the hospital restored it, and also his health.

“Every single nurse, doctor, food prepared, the people who cleaned the bathroom, not just at St. Francis Hospital, but across this country,” he said. “I learned when I was in that hospital laying on that bed—I couldn’t even clean myself—that those people checked on me around the clock, I watched their stress, I watch their tears. But at the same time I watched their joy when one person like me was saved.”

Though Ed Dubose wasn’t one of Shannon Carson’s patients, cases like his help keep the Wisconsin doctor optimistic in a pandemic.

“We’ve seen patients who we never thought would pull through, we’ve seen them leave the hospital,” Carson said. “And know that at some point, they’re going to be able to return to some sense of normal life from the most severe critical illness that we’ve seen.”

“That gives us all a true sense of purpose.”

Dr. Shannon Carson

A new sense of optimism

Through the dark, there is also a new sense of optimism in the form of vaccines.

“You know, it just happens to be a lot of resources piled into this vaccination,” Martinelli said. “And I think that we’re seeing the results of that. So, no steps were skipped. Seems pretty safe. I would take it.”

In fact, every medical professional we asked said that they would take the vaccine.

“First chance I get, just to help me relax a little bit, at least on that aspect of it. And also to do my part as a citizen to reduce the level of potential virus in the community,” Carson said.

Sheehy said, “I will take the vaccine while I want to offer it. I believe in science and I think this is what we need to get the virus under control.”

There is no last word on COVID-19, but it was Wisconsin nurse Alex Martinelli who summed it up best:

“I think at the end of the day, being able to disseminate to people that this is real,” he said. “People are very sick. This is not something where you can only get it if you’re old or immunocompromised. It’s really just a roll of the dice of how it’s going to affect you, so I think that we all have to do our part to protect one another because you just don’t know there is so much unknown about this.”