BROOKS COUNTY, Texas (Border Report) — On a windswept ranchland full of rattlesnakes and prickly pear cactus and illuminated only by a rising moon, Luis Alberto Paredes emerged limping and struggling.

The 34-year-old Guatemalan had been lost in the brush for five days without food. His two friends left him when he couldn’t keep up, he told Border Report on Friday night in a remote section of South Texas where many migrants have died trying to get around a U.S. Border Patrol checkpoint.

Paredes was spotted on surveillance cameras walking in circles on a 20,000-acre cattle ranch wearing blue jeans and a hooded sweatshirt, carrying only a small bottle of water.

His knees could not bend. His eyes rolled back as he spoke. And he barely had the energy to talk before a Border Patrol agent took him away.

Paredes said he was grateful to God for the ranch’s private security guards, who spent four hours searching for him well into dark.

“It’s my first time coming. But I couldn’t keep going with my friends. My knees hurt and they left me, but thank God for the men who found me out there,” Paredes said in Spanish, clutching a tattered silver tent cloth that he said he used to sleep.

The security guards found him about 70 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border. He was 16 miles northeast of the Border Patrol checkpoint that is located south of the small town of Falfurrias, Texas, in an area dense with brush that migrants must traverse if they are to have any hope of making it to the interior.

With Border Patrol agents, state troopers, and law enforcement personnel concentrating on an area along the Rio Grande about an hour’s drive south to help with the overwhelming influx in migrant families and unaccompanied migrant youth crossing from Mexico, desolate regions of Texas farther north, like rural Brooks County, often contend with a harsher reality: Recovering the bodies of migrants hopelessly lost in an unforgiving terrain.

South Texas for years has had the most migrant deaths of any Southwest border area, and with law enforcement now preoccupied to the south, officials fear many more will die here.

Human traffickers known as coyotes are taking advantage of the diversion in law enforcement forces to try to move more migrants north through this dangerous region. This includes mostly single adults, who under the Biden administration’s current policies and travel restrictions implemented due to coronavirus pandemic, are not allowed to enter the United States.

That puts the migrants and these communities at risk, Texas state Sen. Juan “Chuy” Hinojosa, told Border Report.

“A lot of the people coming across are adults, without children, that are being smuggled through the gaps that are being left unprotected by Border Patrol who are dealing with the children,” said Hinojosa, a Democrat who represents this area.

Another day without food or help and Paredes likely would have died, said Brooks County Sheriff’s Patrol Deputy Roberto Castañon, who gave Border Report an exclusive overnight ride-along Friday during his 12-hour shift through this rural county.

“He’s lucky because much longer and he wouldn’t have been walking out,” Castañon said,

As the only Brooks County sheriff’s deputy on duty that night, Castañon was called to the ranch and fetched Paredes and drove him to the entrance where he was transferred to an awaiting Border Patrol agent who took him for medical care.

“They’re usually compliant. Especially when they’re giving up. All they want is just help and they’re trying to get caught. The ones who are not compliant they usually run away from you,” Castañon said.

The irony of this apprehension is that Paredes wasn’t even rescued in Brooks County. He was found in neighboring Kleberg County. But because this region is so vast and remote and law enforcement agencies are stretched so thin, they all help one another out, Castañon said as he drove his SUV through the dimly moonlit night.

Castañon said he has retrieved the remains of many migrants, mostly from Central America, who lost their way in the brush and died from dehydration, rattlesnake bites, or were attacked by wild boars or coyotes when they rested or slept or were propped beneath mesquite trees to nurse injuries.

He describes how swollen their faces get and the purple and dark marks that form on their skin. He can usually tell how long they have been dead; if they were “soft” they had recently passed. Castañon talks about zipping them into body bags, showing up for his next shift, and the possibility of doing it all over again the very next day.

As triple-digit temperatures arrive and the hot, punishing South Texas sun beats down, Castañon fears he will be called out to retrieve more remains as more and more undocumented migrants continue to cross in this area.

He blames it all on the coyotes, human traffickers affiliated with drug cartels who know this region well and who even hire children to drive the migrants north from the Rio Grande Valley and then drop them off as close to the eight-lane Border Patrol checkpoint as they can. The migrants are then forced to navigate — often at night and by foot — around immigration authorities to areas north of the checkpoint to meet up with other coyotes, who take them to the interior of Texas.

In order to go around the checkpoint, the migrants — mostly adults — must cross through private properties and trek through the thick cactus and mesquite trees and soft, sandy soil. Some break into ranch trailers looking for food or shelter, Castañon said. Others die as they walk for days headed toward a “pinpoint” that coyotes have put on a cellphone they’ve been given. If they don’t reach the pickup zone in time, like Paredes, they are left behind.

Earlier this month, in an area south of the checkpoint, Castañon said he stopped a car driven by a 13-year-old boy transporting seven undocumented migrants. Castañon said it was the second time the boy from Mission, Texas, had been arrested, but charges weren’t brought against him because he is a minor, and he refused to talk with law enforcement.

Castañon said the cartels are crafty and hire people who know where to go and what not to say or do if arrested. Many will drive through ranchlands to evade arrest, he said, often endangering residents and livestock, damaging fences and property, and putting migrants at risk.

Brooks County Sheriff Urbino “Benny” Martinez told Border Report that his deputies regularly are involved in high-speed chases with smugglers and “bailouts,” in which smugglers ditch their vehicles and the migrants scatter into the brush.

A similar chase ended fatally two weeks ago near Del Rio, Texas, when a pickup carrying migrants slammed head-on into another truck, killing eight migrants.

Sometimes, out of desperation, migrants will jump on the roof of resting 18-wheelers in hopes of making it north.

Castañon said a delivery truck driver parked to rest near a weigh station two weeks ago “and a migrant got on his roof. He called 911 after he found the migrant wedged in a compartment on his roof.” Castañon says they have found as many as three migrants crammed in spaces barely big enough for one adult.

They also have found hidden compartments carved into the hundreds of cars confiscated by the Brooks County Sheriff’s Department, which are on an impound lot waiting to be auctioned.

It is a game of numbers — how many they are, how few the Border Patrol and law enforcement agents are, and how vast the countryside here is. The coyotes are betting the numbers favor the migrants, and are willing to bet their lives.

“The complaints we are receiving from many of the residents on the border are real. The immigrants are coming across and most of Central America thinks the border is open,” Hinojosa said. “But there’s also a danger to them because many of them get disoriented in the brush, and they don’t have any water or any food. They’re not protected from the elements. So it is really not a very good situation that we’re facing right now.

“And what we’re seeing right now is just the tip of the iceberg. What we can anticipate is going to happen in the months ahead as the weather changes,” Hinojosa said.

With fewer than 7,000 residents, most of the residents in Brooks County own or work on cattle or hunting ranches. It’s a sparsely populated place in South Texas where the ranches span thousands of acres and where residents like their privacy and treasure peace and quiet.

But many of these ranches and fields are littered with water jugs, shoes, backpacks and remnants from where migrants have camped. Some areas smell of urine where security guards say massive groups of migrants camp nightly.

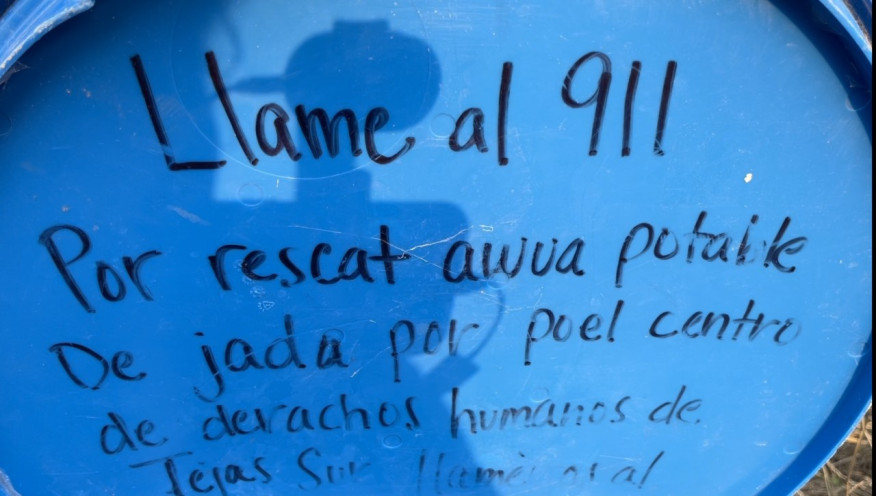

Volunteers with the nonprofit South Texas Human Rights Center have put up 175 water stations throughout the region, a volunteer told us. The water is replenished as quickly as it can but sometimes not quick enough.

From 1998 to 2019, more than 3,243 migrants died in South Texas according to a May report by the University of Texas at Austin’s Straus Center “Migrant Deaths in South Texas.”

“Today more migrants die in South Texas than anywhere else in the country,” the report says.

Paredes, the migrant found Friday night, said he survived because of the water he found in the familiar blue “agua” containers. Some containers have 20-foot-tall blue flags so they can be more easily spotted by migrants.

The volunteers must negotiate with private ranchers for permission to place the water containers and not all are willing.

Many ranchers hire their own private security guards. Most do not allow Border Patrol onto their lands, said Castañon, who is allowed on as the county sheriff’s deputy and works hand in hand with the other law enforcement personnel.

The security guard who found Paredes on Friday night wished to remain anonymous. He said his boss is private and does not allow media onto the property.

On his cellphone, the private security guard scrolled through photos taken from cameras on the property showing dozens of migrants crossing, mostly walking in single-file through the waist-high brush and soft, sandy terrain. On Wednesday night, a rattlesnake bit a migrant, and another migrant carried him to them, he told Border Report.

Castañon said about 95% of all migrants he encounters say they were trying to get to Houston. “They’re not trying to get to San Antonio or Austin. It’s always Houston,” he said.

With so many places to hide, so much land and so few agents, the human traffickers are taking advantage of this current immigration swell on the border, said Castañon.

“If I don’t stop them then they’ll make it past the checkpoint,” he said as he waited at a familiar spot where he has apprehended several migrants south of the Border Patrol checkpoint.

Latest News

- AUTO TEST: Blocks – Checking Link Group Sharing block

- AUTO TEST POST 20241212231237

- AUTO TEST POST 20241212231151

- AUTO TEST POST 20241212230901

- AUTO TEST POST 20241212200036

Texas troopers used to line Highway 281 at one-mile intervals leading to the Border Patrol checkpoint, and border agents filled in the gaps and hunted migrants off-road in the fields, Castañon said. But Texas Gov. Greg Abbott earlier this month announced Operation Lone Star, which, so far, has resulted in 1,000 additional state troopers deploying further south in the Rio Grande Valley.

Aside from rescuing and tracking migrants, Castañon’s duties are vast and varied and include regularly having to assist ranchers to get cattle and goats back in their fences. The fences often are damaged by smugglers during pursuits, and aside from costing ranchers a lot in repairs, large livestock could severely damage vehicles or even kill motorists if they come upon them in the dead of the night.

Castañon puts upwards of 300 miles on his vehicle every night, mostly driving up and down Highway 285, which runs east to west into Kleberg County, as well as caliche and dirt backroads, where he often comes upon wild dogs, coyotes, and wild boar.

During last month’s deep freeze, three migrants flagged him down on Highway 285.

“One had icicles in his hair,” Castañon said. It was 27-degrees out and windy. “They just gave up and jumped into my vehicle,” he said.

His flashlight is his go-to equipment in the darkness and he says usually the animals leave him alone.

As he patrols for miles, kicking up dust and rocks and scraping paint from his vehicle on mesquite tree branches, his radio crackles with a dispatcher announcing they have a “walker” on the radio. A group of migrants have been spotted far north in the county.

But as he races miles to get there, dispatch reports that the “walkers” have migrated into Jim Wells County, the next county north, and they have lost sight of them.

He turns his vehicle around and heads back to sit and wait at the spot south of the checkpoint. He will wait there past 3 a.m.

“We’re helping them. They need help as soon as they can,” he says as he shakes his head wondering if that group will make it safely by daybreak. “It gets to me because I have a 2-year-old,” he said. “I wonder about their families.”