Ex-officer Kim Potter failed Daunte Wright, prosecutor argues

Testing on staging11

MINNEAPOLIS (AP) — A suburban Minneapolis police officer who said she mistakenly drew her gun instead of her Taser when she fatally shot Black motorist Daunte Wright went on trial on manslaughter charges Wednesday, with a prosecutor saying Kim Potter had been trained how to avoid such deadly mix-ups but still got it wrong.

Potter’s lawyer, though, argued that she made an error, saying, “Police officers are human beings.” And he appeared to cast blame on Wright, saying all the 20-year-old had to do that day was surrender.

Potter, 49, is charged with first-degree and second-degree manslaughter in Wright’s April 11 death in Brooklyn Center. The white former officer, who resigned two days after the shooting, has said she meant to use her Taser on Wright, who was Black. Her body camera recorded the shooting.

Wright’s mother, Katie Bryant, testified about the moment she saw her son lying in his car after he’d been shot. She said she tried to contact him through a video call after losing an earlier phone connection, and that a woman answered and screamed, “They shot him!” and pointed the phone toward the driver’s seat.

“And my son was laying there. He was unresponsive and he looked dead,” Bryant said through tears.

A mostly white jury was seated last week in the case, which sparked angry demonstrations outside the Brooklyn Center police station last spring as former Minneapolis Officer Derek Chauvin was on trial just 10 miles (16 kilometers) away for killing George Floyd.

Defense attorney Paul Engh told jurors that Potter made a mistake when she grabbed the wrong weapon and shot Wright after he tried to drive away from a traffic stop while she and other officers were trying to arrest him.

Engh said all police had reason to believe that Wright might have a gun and that all he had to do was surrender. And he said Potter “had to do what she had to do to prevent a death to a fellow officer” who had reached inside Wright’s car and was at risk of being dragged if Wright drove away.

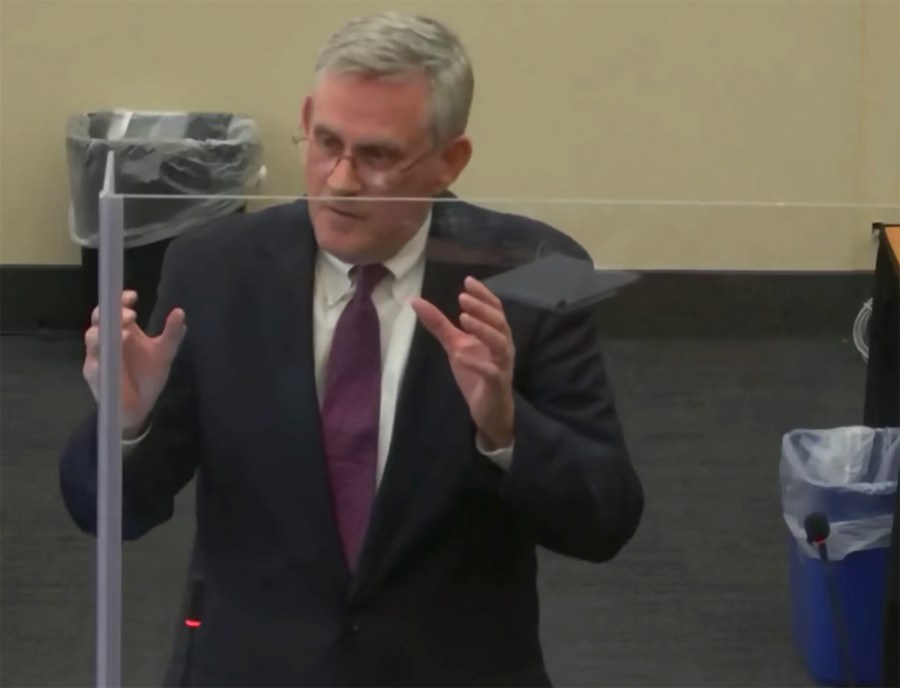

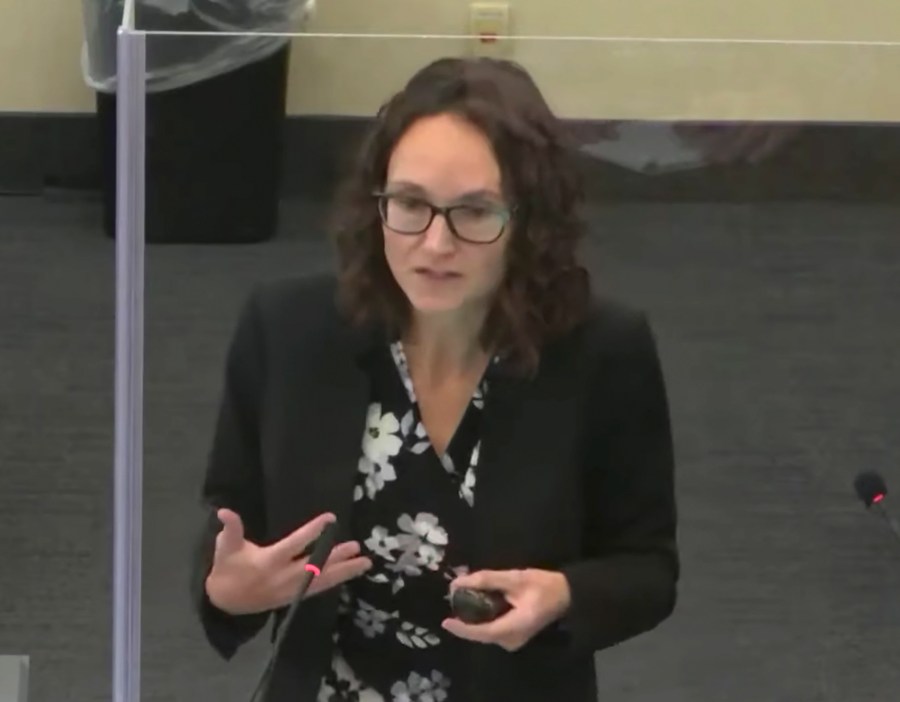

Prosecutor Erin Eldridge earlier told jurors that Potter violated her extensive training — including on the risks of firing the wrong weapon — and “betrayed a 20-year-old kid.”

“This is exactly what she had been trained for years to prevent,” Eldridge said. “But on April 11, she betrayed her badge and she failed Daunte Wright.”

“We trust them to know wrong from right, and left from right,” Eldridge said. “This case is about an officer who knew not to get it dead wrong, but she failed to get it right.”

Potter, who has told the court she will testify, was training a new officer when they pulled Wright over for having expired license plate tags and an air freshener hanging from the rearview mirror, according to a criminal complaint.

When they found that Wright had an outstanding warrant, they tried to arrest him but he got back into his car instead of cooperating. Potter’s body-camera video recorded her shouting “Taser, Taser, Taser” and “I’ll tase you” before she fired once with her handgun.

Eldridge played extended body-camera video from the shooting for the jury, including the moments right after Potter shot Wright.

Her camera recorded her saying ”(expletive) I just shot him” and “I grabbed the wrong (expletive) gun.” After his car rolls away, it shows Potter sink to the curb and sit down, further exclaiming “Oh my God.” Defense attorneys argued in pretrial filings that her immediate reaction bolsters their argument that the shooting was a tragic accident.

Engh said that during the stop, the officer-in-training smelled marijuana. He also said Wright didn’t have a license and gave the officer an old proof of insurance that was under another name.

There also was a warrant for Wright’s arrest on a weapons charge, which Engh said led that officer to believe that there was a “substantial chance” that Wright had a gun in the car — he was unarmed — and that officers had no choice but to arrest Wright. There was also a restraining order against Wright, the defense lawyer said.

“A court of law directed him to arrest him!” Engh shouted while pounding on the courtroom lectern. He told jurors it wasn’t about expired tags by that point, and that officers also had to make sure the woman in Wright’s car was OK because of the restraining order.

He said this was standard police work and that Potter made an error.

“We are in a human business. Police officers are human beings. And that’s what occurred,” Engh said.

But defense attorneys also have asserted that Potter was within her rights to use deadly force if she had consciously chosen to do so because Wright’s actions endangered other officers.

Prosecutors say Potter had been trained on Taser use several times during her 26-year police career, including twice in the six months that preceded the shooting. They say Potter’s training explicitly warns officers about confusing a handgun with a Taser and directs them “to learn the differences between their Taser and firearm to avoid such confusion.”

Eldridge told jurors that officers are required to carry their Taser on their non-dominant side and their firearm on their dominant side. Potter carried her gun on her right and her Taser on her left.

Officers can choose to position their Tasers in their duty belts so they can either draw it from across their body with their dominant hand or draw it with their nondominant hand. Potter had hers positioned in a “straight draw” position, so she would draw it with her left hand.

“The only weapon she draws with her right hand is her gun, not her Taser,” Eldridge said.

The prosecutor told jurors they would hear about several policies that she says Potter violated, including one that says flight from an officer is not a good cause to use a Taser.

A jury of 14 people, including two white alternates, will hear the case. Nine of the 12 jurors likely to deliberate are white, one is Black and two are Asian.

The most serious charge against Potter requires prosecutors to prove recklessness, while the lesser requires them to prove culpable negligence. Minnesota’s sentencing guidelines call for a prison term of just over seven years on the first-degree manslaughter count and four years on the second-degree one. Prosecutors have said they will seek a longer sentence.